Nonprofit Revenue Diversification

We’ve all heard the adage, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” How does this advice hold up for nonprofit income?

We’ve all heard the adage, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” How does this advice hold up for nonprofit income?

Before we continue our Nonprofit Chart of Accounts Grand Tour into income accounts (here’s the guide to the Tour of balance sheet accounts), first let’s consider the concept of income diversification. Income accounts can vary widely from one nonprofit to the next based on the nonprofit’s sources of income.

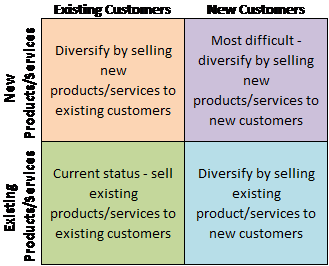

To introduce income diversification, we will first consider classic for-profit diversification.

For-profit businesses create new income streams by combining existing and new products/services with existing or new customers. For example, a grocery store adds a pharmacy to serve existing customers. Home delivery, a new service delivering existing products, enables them to reach new customers. The idea is not just to make more money, but to be more resilient in the face of downturns that may affect an industry, customer group, or the economy as a whole.

Nonprofits immediately run into a problem – offering more products and services or serving more customers typically leads to more losses. (A good accounting system will help you determine profit or loss on a particular program service. That’s a topic for another post!) Nonprofit programs often exist because they are not profitable for the market to pursue.

Adding another complication, the payer is often not the same as the customer. Individuals who benefit from nonprofit services often pay below market price or nothing for those services. Other nonprofits may benefit society as a whole, for example environmental or animal rights organizations, and have no direct customers to charge. Income depends on what payers are willing to pay for as opposed to what customers want to buy.

Under these realities, how can nonprofit organizations diversify income? Here are several ideas.

1. Add a mission-based product/service offering that provides income.

For example, an organization devoted to saving wildlife could offer fee-based lectures or public speakers to educate the public about protecting endangered species. The same organization could also offer merchandise with the organization’s logo, wildlife pictures and messages to increase public awareness.

2. Take advantage of activities specifically exempt from tax.

Some organizations operate a thrift store to sell donated merchandise. Other organizations that own their buildings with no mortgage rent space. For example one organization rented a room to a small church every weekend. (In Florida, be aware of sales tax rules on commercial rentals.) Many organizations hold annual fundraising events.

3. Develop new ways to raise contribution income.

An organization with government grants could begin to cultivate private contributions, which offers more flexibility than government funding. An organization with a base of regular donors could begin the process of soliciting major gifts. These are large gifts (relative to donation amounts the organization normally receives) that may take months or years of communications. The organization could begin researching and cultivating relationships with private foundations. Perhaps the organization could explore a cause related marketing partnership with a for-profit company where the company donates a percentage of product sales. And don’t forget about in-kind contributions!

4. Seek endowment gifts to generate investment income.

An endowment is created when a donor makes a gift with instructions to preserve the original gift and only spend the investment earnings it produces. Endowments are often created from bequests. Investment earnings are not taxable income for public charities. Sometimes the donor places a restriction on how endowment earnings may be spent; other times the investment earnings can be used in any way the organization sees fit. Organizations that receive a large unrestricted gift or that accumulate a large amount of cash may also decide to set aside funds to function as an endowment. While an endowment may seem out of reach for a small nonprofit, we don’t think it can hurt to ask your donors to remember your organization in their wills!

5. Earn unrelated business income subject to income tax.

A nonprofit that offers therapeutic horseback riding lessons to autistic children considered expanding to offer lessons to the general public. Conducting an activity more broadly than necessary to fulfill the organization’s charitable purpose creates taxable income. Nonprofits are allowed to generate taxable income as long as it is not a substantial portion of their overall income. (Click here for an excellent article from Hurwit & Associates on unrelated business income.) Ultimately this idea was not pursued, but it was a great idea since they had capacity to teach more students.

6. Do some combination of the above.

The nonprofit that offers therapeutic horseback riding lessons decided to diversify by offering their existing service to new customers — veterans suffering from PTSD. This strategy used the same fixed assets (horses, equipment, barn) and instructors to expand into a new program area that was still related to the organization’s mission of helping people with special needs. The key to new revenue was developing income from third parties who were interested in funding the veterans’ program. For example, the organization received funding from an area university studying alternative treatments for veterans with PTSD. This new program area also attracted private donations.

New funding sources, whether earned or contributed, take time to develop and administer. Skills need to be learned, relationships developed and accounting processes put into place. The reality is that a new funding source can take years of patient work while diverting administrative resources from program operations and other revenue producing activities. This is the hidden cost of income diversification.

A Study of Fast Growing Organizations

Bridgespan Group did a study in 2003 focused on fast growing youth services and environmental organizations. (The largest charities, health and education organizations, were excluded from this study.) They found the organizations went through distinct transitions as they grew. They began with a few funding sources, transitioned to more diverse funding sources, and once they surpassed $10 million in revenue, returned to a few concentrated funding sources.[1]

Bridgespan found the environmental groups in their study under $1 million in revenue received about half of their funding from private foundations with the balance coming from individuals and other sources. Youth services organizations at this level received about a third of their income from private foundations and the rest from earned income and other sources. As the organizations exceeded $1 million in revenue, they were more likely to incorporate government funding.

The reliance on private foundations by organizations in the earlier stages of growth is interesting. Out of total private contributions, foundation giving only makes up about 15%. (See the GivingUSA analysis here.) We’ve often heard advice to focus on individual contributions because they make up 80% of private charitable giving. However, based on this study and our own clients, private foundations appear to play a significant role in supporting smaller nonprofit organizations.

Conclusions on Diversification for Small Nonprofits

Last week we spoke with a foundation manager who lamented the poor state of financial reporting by many of the organizations the foundation wanted to support. He told us that before they could give grants to some of these organizations, they needed to improve their financial reporting and management capabilities. Part of that process, of course, means putting a good financial accounting system in place.

The lesson for organizations, especially organizations under $1 million in revenue, is to focus on doing an excellent job with a few income sources. Investigate similar organizations in terms of revenue size and industry to see how they fund their operations. Brainstorm income ideas. Then be strategic in choosing which income sources to pursue and be realistic about the related administrative costs. Develop the in-house capacity to manage and account for the sources of income you decide to focus on.

It may seem counter intuitive to divert attention from programs while increasing focus on management (see our nonprofit accounting solution) and fundraising capacity. Nonprofits that are successful in diversifying income know the value of excellence in execution. This means excellence in program execution as well as management and fundraising execution.

Don’t simply do more things. Do things well.

[1] William Foster, Ben Dixon, and Matt Hochstetler, “In Search of Sustainable Funding: Is Diversity of Sources Really the Answer?” The Nonprofit Quarterly (Spring 2007)